Skin health and wound problems

Fish live in water. This means that in practice they are swimming in everything that could potentially cause diseases. The skin and mucous membranes are the only things that separate the inside of the fish from their surroundings, and an intact barrier of skin will therefore be key to the first-line defences of the fish against disease.

This barrier of skin can be weakened by a variety of different means, of both mechanical and infectious origin. In addition to the significance of a rupture in the skin barrier in terms of resistance to disease and fluid balance, wounds in the skin of the fish will be a challenge in terms of fish welfare.

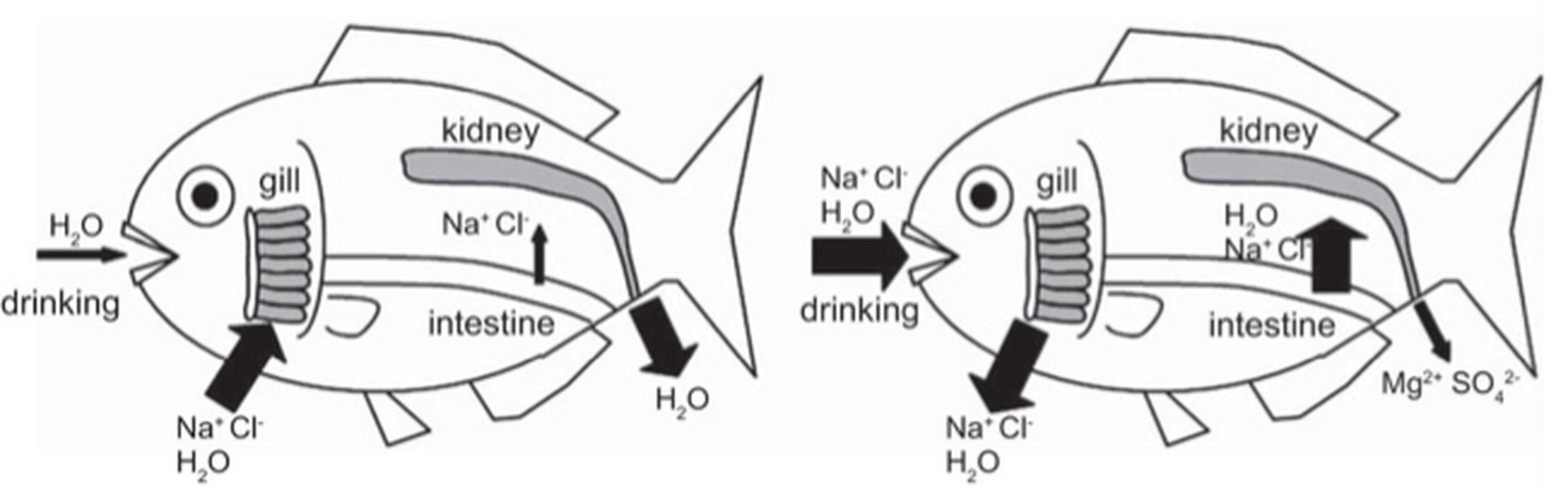

In freshwater, the inside of the fish will be saltier than the surroundings. This means that water is being forced into the fish all the time, and to maintain its fluid balance, the fish must excrete water via diluted urine, and gather as much salt as possible from the surroundings via pumps in the gills, and from feed via the intestines.

In saltwater, the inside of the fish will be less salty than the surroundings. This means that water is constantly seeping out the fish and it is in danger of dehydrating.

This means that the fish must drink large quantities of water and excrete concentrated urine. It also actively excretes salts through the gills via the NA/K and chloride channels in the gills. It is the activity in this respect that we measure when we check whether the fish is ready to be put out to sea.

If there is a rupture in the skin, the water will seep in quicker via the barrier and the fish has to work harder to maintain the fluid balance.

In addition to being important for the salmon's defences against disease, the skin also plays a key role in the regulation of the fluid balance. Salmon in saltwater are in constant danger of drying up, and in freshwater are in danger of being steeped. For the skin to be intact is an important part of the protection against this effect.

Specialised cells in the skin make an active contribution to the defence mechanisms against infection agents and mechanical wear and tear.

Skin cells

The salmon's skin cells have many special functions. They are migratory cells that can quickly cover small wounds. They can also absorb bacteria and destroy them through a process called phagocytosis.

Mucous cells

Mucous cells produce a special mucous with antimicrobial and mechanical properties that covers the skin and acts as a protective barrier against both infection agents and mechanical wear and tear.

Shell

The salmon's skin is covered by a layer of hard shell. This acts as armour and is also an important mineral store for the fish in the same way as the skeleton is.

Immune cells

If the skin barrier is ruptured, the immune cells deep down in the skin will get ready to attack any infection agents. The immune status of the fish will be crucial with respect to how many immune cells there are and how effective they are.

Mechanical wounds

Over recent years, mechanical damage to the skin has become more widespread.

This can partially be explained by the increased use of non-medicinal mechanical methods to control salmon lice, which means that the fish have to be pumped from the cages and into well-boats for treatment.

In addition, there has been increased wear and tear to the skin and mucous layer due to the use of hydrogen peroxide as a delousing agent. If these treatments are performed at low temperatures, this can increase the chances for the development of wounds as all the biological processes in salmon, including wound healing, occur more slowly at low temperatures. Mechanical wounds can act as entrance points for bacterial wound infections.

Bacterial wound infections

The salmon's skin is exposed to bacterial infections that can lead to very serious wounds.

Different bacteria are associated with wound problems, and both the classic winter bacterium Moritella Viscosa and the bacteria Tenacibaculum ssp and Aliivibrio Wodanis are frequently isolated from wound infections in salmonids. These are often observed together in wounds, and there is a lot of evidence that the composition will be key for the degree of severity. Which problems arise vary to such a degree that we talk about different "syndromes", classic winter wounds, and atypical bacteria wounds.

Classic winter wounds

Facts

Classic winter wounds are first and foremost seen in the context of the bacterium Moritella Viscosa. This bacterium thrives best in cold water, and it is at lower temperatures (below 7-8 degrees C) that they grow quickest and produce toxic substances that are harmful to the skin.

The wounds are general located on the side of the salmon, and range from surface wounds that are unproblematic to deep and serious wounds that can protrude into the peritoneal cavity of the salmon.

The consequences of wounds can therefore range from limited to major losses due to increased mortality. They can also lead to economic consequences in the form of downgrading of fillets in the slaughterhouse due to a deterioration in quality. Winter wounds are very infectious and quickly spread between fish in the cage.

Occurrence/prevalence

Winter wounds are not uncommon in Norway today, and there is a tendency for the occurrence to be greater in the north of the country.

This can be seen in connection with the fact that the water temperatures are generally lower in this part of the country. It is difficult estimate accurately the occurrence of the disease as it is not reportable.

Symptoms

Outbreaks of winter wounds are characterised by many fish in the cage having the characteristic wound on their sides, of different sizes and degrees of severity.

Diagnosis

Winter wounds are diagnosed based on the symptoms.

Prevention/treatment

Vaccines are routinely administered against Moritella Viscosa., This vaccine has a preventive effect against the development of winter wounds, but does not provide 100% protection.

It is important to ensure that the fish have as few lice as possible, and are as healthy as possible before the temperature in the water falls below 8 degrees. Prevention through operational arrangements and feeding before risk periods can contribute to the prevention of winter wounds.

Atypical bacterial wound infections

In addition to the classical winter wounds, we observe that bacterial wound infections can also occur in warmer waters that often manifest themselves as head and jaw decay, and fin and tail rot. These wounds are often serious, and in some cases, whole parts of the body can be destroyed by bacteria. The most common bacteria in wounds is a family of malignant bacteria called Tenacibaculum Ssp. There is a lot of evidence that Tenacibaculum is widespread, and that they are opportunistic bacteria that attack when the skin barrier of the fish is weakened. Prevention is the same as for classic winter wounds, operational arrangements and the strengthening of the fishes' own defences against bacteria.

Prevention of wounds with adapted feed

Feed can help to strengthen the skin barrier in different ways.

Feed that supports the immune system of the fish will also contribute to stronger skin, as the immune status of the fish will be crucial for the outcome of wounds if the skin barrier is ruptured.

The creation of a thicker and more effective layer of mucous will be positive for the skin by protecting the skin from mechanical stresses, and against infections involving bacteria and lice. The mucous layer is especially important given the current situation with lice as a thicker mucous layer can make it more difficult for lice to penetrate through the skin to become established. Lice will again be important for wound development as they can perforate the skin and create small wounds in the skin that can be entrance points for wound bacteria.

Fish that are starving use minerals from the shells to maintain the mineral balance. Feed that stimulates the appetite of the fish can make the fish increase its feed intake quicker after periods of starvation, and can maintain feed intake through periods where there is a danger of reduced feed intake, and thus contribute to keeping the shells strong.