BioMar has significantly reduced its consumption of marine ingredients by 70% in the last 30 years. While these ingredients remain a great nutrient for fish and shrimp diets, they must be responsibly sourced from healthy fish stocks.

The most recent report from the Sustainable Fisheries Partnership (SFP) on the health of fish stocks used for marine ingredients shows that 4% were rated very well managed, 75% reasonably well managed, and 21% poorly managed.

Fishery Improvement Projects

BioMar recognises that “reasonably well managed” is likely insufficient protection against the intense fishing pressure and human-induced habitat changes that most global fisheries face. Moreover, a poor management rating for one out of every five fish stocks in the assessment is unacceptable.

BioMar wants to drive improvements in fisheries management so that poorly managed fish stocks move up to reasonably managed. The long-term goal is that the majority of fish stocks are very well managed. The fishery improvement project (FIP) models of MarinTrust and FisheryProgress are designed for that express purpose.

FIPs are multi-stakeholder initiatives that identify and address the gaps between the current status of a fishery vs a limited set (basic FIP) or the complete set (comprehensive FIP) of the Marine Stewardship Council (MSC) indicators.

Since 2007, FIPs have increased from 6 to more than 250. This growth comes from the sustainable food systems movement and an increased focus on humans’ negative impacts on oceans, where overfishing is the most severe and direct example.

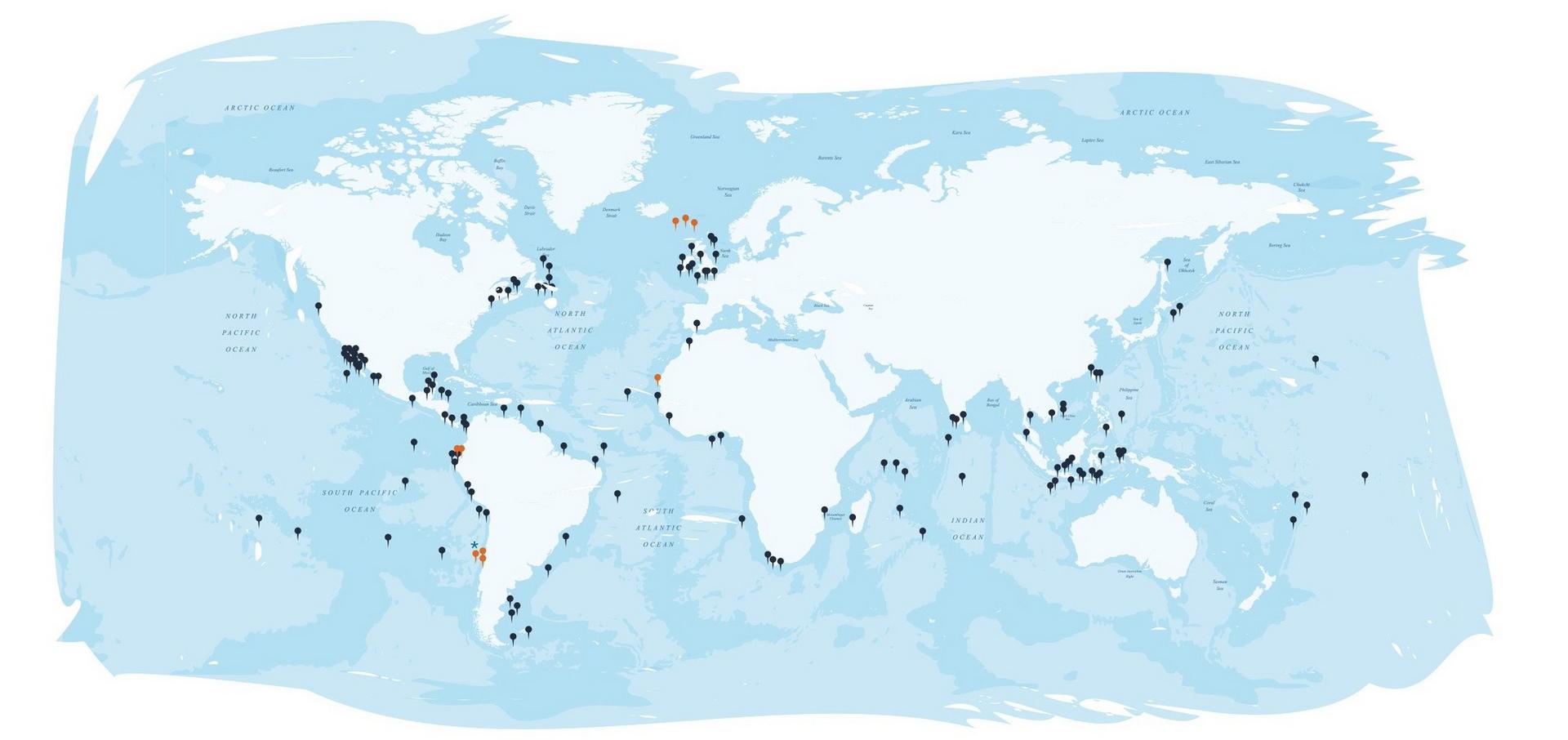

Most of the world’s best sustainable fisheries, as shown in the figure above by MarinTrust and the MSC, are located in developed nations. This figure also shows that most of the global FIPs are located closer to the equator in less developed countries.

The geographical misalignment of sustainable fisheries occurs because less developed countries often need more institutional and scientific support than that required by ecosystem-based fisheries management.

FIPs alleviate this problem through capacity building, technology and knowledge transfer, premium market access, and foreign investment. If executed correctly, the FIP model and its supply-chain incentives can bring about positive human development in countries especially vulnerable to overfishing and depleted fish stocks.

The FIP participatory ecosystem must contain the right mix of stakeholders

The Conservation Alliance for Seafood Solutions (CASS) has published guidelines for supporting FIPs since 2012. CASS recommends including, at a minimum, the following types of stakeholders in FIPs.

Fishers or groups representing them (producers)

Supply chain actors (BioMar)

NGOs such as Sustainable Fisheries Partnership, World Wildlife Fund, etc.

Scientific experts and researchers

Governmental organizations, such as the Ministries of Fisheries/Labour/Natural Resources, etc.

This requirement allows for capacity building and information exchange between fisheries stakeholders on opposite ends of the power structure spectrum: rights-holders (i.e. workers and communities) and duty-bearers (i.e. authorities and industry).

Social impact assessment in FIPs

A common and fair critique of the historical FIP model of transformative fishery change is that FIPs have not addressed social impacts. BioMar agrees with FIP information manager FisheryProgress that preventing and mitigating human rights abuses in seafood supply chains requires a systemic approach.

FIPs must begin addressing their human rights risks immediately. However, we understand that the perfect cannot be the enemy of the good.

BioMar began contributing to implementing the new Human Rights and Social Responsibility Policy published by FisheryProgress in December 2022 for any new Fishery Improvement Project (FIP) we join.